Alexandre Verbitski, Anurag Gupta, Debanjan Saha, Murali Brahmadesam, Kamal Gupta, Raman Mittal, Sailesh Krishnamurthy, Sandor Maurice, Tengiz Kharatishvili, and Xiaofeng Bao. 2017. Amazon Aurora: Design Considerations for High Throughput Cloud-Native Relational Databases. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD/PODS'17), ACM, 1041–1052. [scholar]

Alexandre Verbitski, Anurag Gupta, Debanjan Saha, James Corey, Kamal Gupta, Murali Brahmadesam, Raman Mittal, Sailesh Krishnamurthy, Sandor Maurice, Tengiz Kharatishvilli, and Xiaofeng Bao. 2018. Amazon Aurora: On Avoiding Distributed Consensus for I/Os, Commits, and Membership Changes. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD/PODS '18), ACM. [scholar]

Disaggregated OLTP Systems

These notes were first prepared for an informal presentation on the various cloud-native disaggregated OLTP RDBMS designs that have been getting published and it cherry-picked one paper per notable design decision. For the papers covered then, I’ve included a summary of the discussion we had after each paper. This page was then extended and re-published to cover all disaggregated OLTP papers, even for papers that are similar between two different vendors.

If you’re looking for a quick overview of the disaggregated OLTP space, just read the papers with a ★.

Amazon

Aurora ★

Read these two papers together, and don’t try to stop to understand all the fine details about log consistency across replicas and commit or recovery protocols in the first paper. That material is covered in more detail (and with diagrams!) in the second paper. I’d almost suggest reading the second paper first.

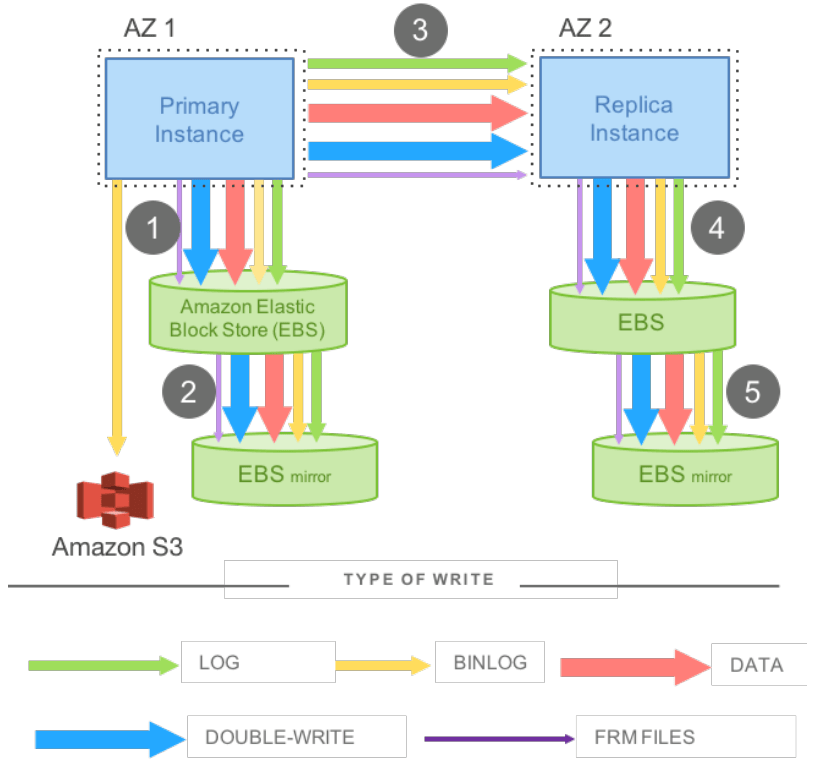

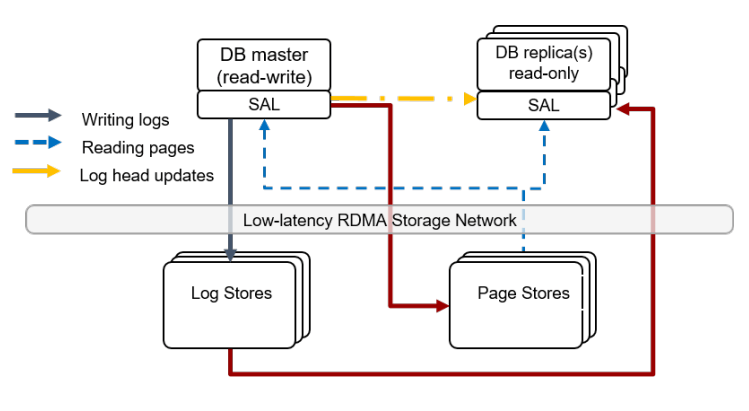

As the first of the disaggregated OLTP papers, they introduce the motivation for wanting to build a system like Aurora. Previously, one would just run an unmodified MySQL on top of EBS, and when looking at the amount of data transferred, the same data was being sent in different forms multiple times. A log, a binlog, a page write, and the double-write buffer write, are all essentially doing the same work of sending a tuple from MySQL to storage.

Thus, Aurora introduces using the write-ahead log as the protocol between the compute and the storage in a disaggregated system. The page writes, double-write buffer, etc. are all removed and made the responsibility of the storage after receiving the write-ahead log. The papers we’re looking at all reference this model with the phrase the log is the database in some form as part of their design.

The major idea they present is that the network is then the bottleneck in the system, and the smart storage is able to meaningfully offload work of processing WAL updates into page modifications, handle MVCC cleanup, checkpointing, etc. By doing this, they’re able to achieve a 35x increase in transactions per second with an 87% decrease in the IO work per transaction. Removing as much of the storage and replication responsibility from the query processing node as possible results in a significantly more capable database.

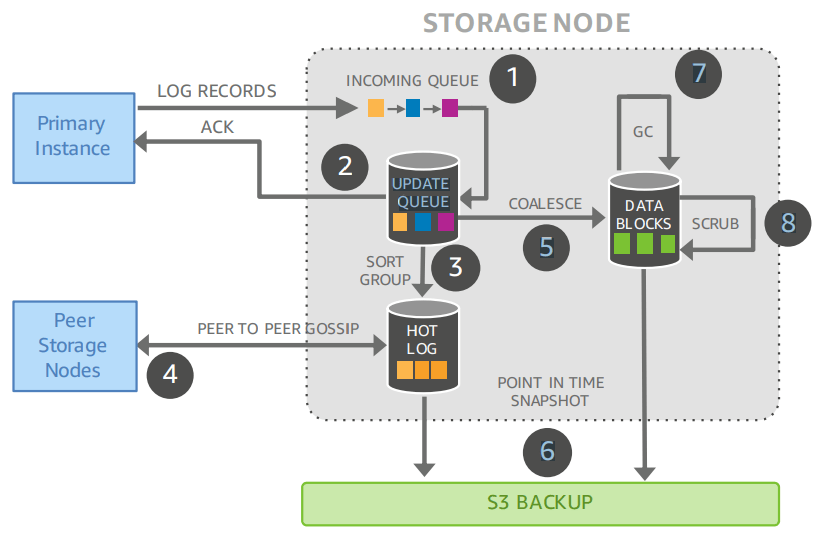

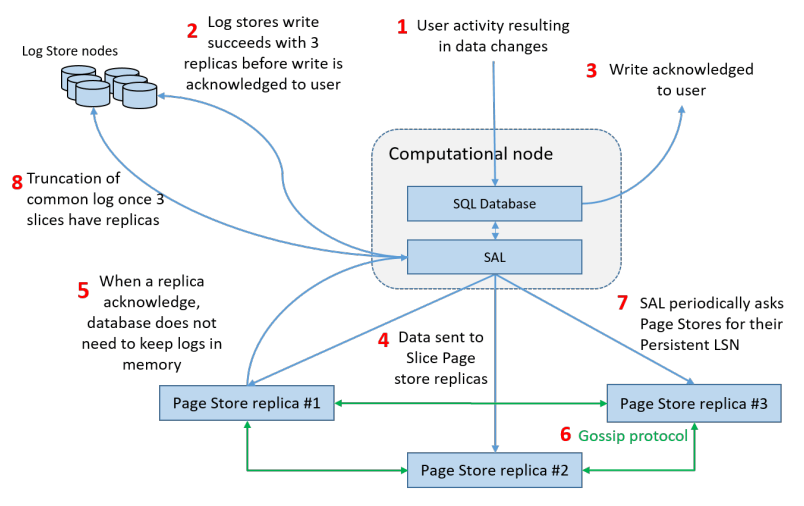

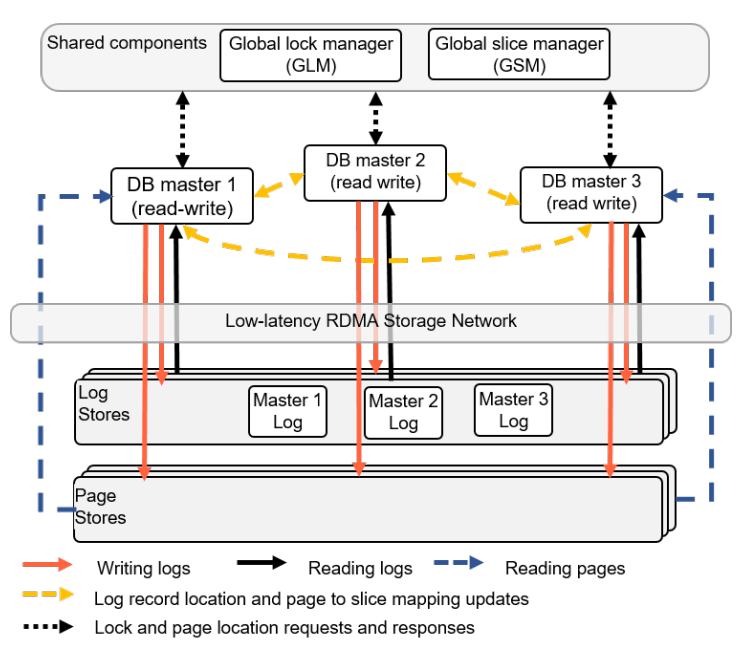

The easiest way to get started on the Aurora architecture is to zoom in on a single storage node:

It involves the following steps:

receive log record and add to an in-memory queue,

persist record on disk and acknowledge,

organize records and identify gaps in the log since some batches may be lost,

gossip with peers to fill in gaps,

coalesce log records into new data pages,

periodically stage log and new pages to S3,

periodically garbage collect old versions, and finally

periodically validate CRC codes on pages.

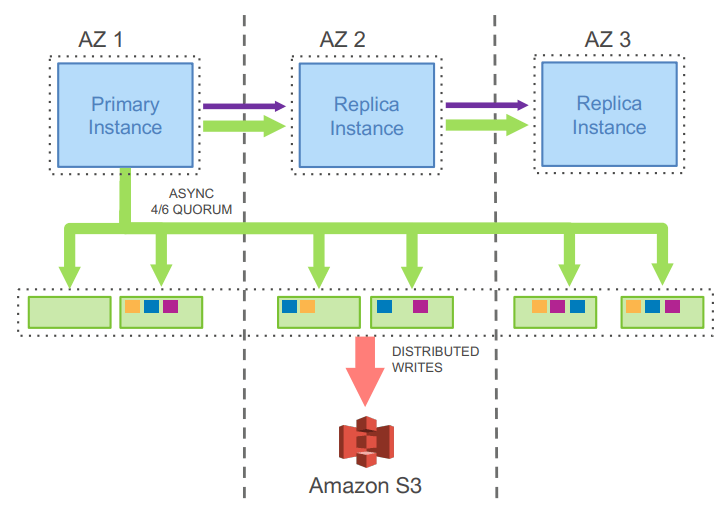

Storage nodes are used as part of a quorum, and the classic "tolerate loss of 1 AZ + 1 machine" means 6-node quorums with |W|=4 and |R|=3. The quorum means that transient single node failures (either accidental network blips or intentional node upgrades) are handled seamlessly. However, this isn’t traditional majority quorums. The Primary is an elected sole writer, which transforms majority quorums into something more consistent. Page server quorums are also reconfigured on suspected failure. This is a replication design that doesn’t even fit cleanly into my Data Replication Design Spectrum blog post.

Each storage quorum is responsible for a partition of data, and the write ahead log is identically partitioned across storage node quorums. This introduces significant complexity in terms of trying to track and identify consistent points in the log when no node has a complete view of the entire WAL. Aurora introduces a full set of new terms to discuss specific log points:

-

LSN: Log Sequence Number, a monotonically increasing value generated by the primary to label WAL entries.

-

VCL: Volume Complete LSN, the highest LSN for which an individual storage node can guarantee availability of all prior log records.

-

CPL: Consistency Point LSN, log records which it is safe for a storage node to truncate all following records. Log truncation during recovery is limited to these.

-

VDL: Volume Durable LSN, the highest CPL that is smaller than or equal to the VCL.

-

SCL: Segment complete LSN, the maximum LSN for which a storage node knows it has received all previous log records.

-

PGCL: Protection Group Complete LSN, the maximum LSN for which at least 4 of 6 storage nodes in a quorum have made durable.

-

PGMRPL: Protection Group Minimum Read Point LSN, the lowest LSN read point for any active request on a database instance. Storage nodes will only accept read requests between PGMRPL and SCL.

Each log write contains its LSN, and also includes the last LSN sent to the storage group. Not every write is a transaction commit, database transactions are sent as a series of mini-transactions, and only the final mini-transaction is a consistent transaction commit (tagged as a CPL). There’s a whole discussion of Storage Consistency Points in the second paper to dig into the exact relationships between the Volume Complete LSN and the Consistency Point LSN and the Segment Complete LSN and a Protection Group Complete LSN. The overall point to get here is that trying to recover a consistent snapshot from a highly partitioned log is hard, and storage nodes try to fill in missing log entries from other storage nodes which requires non-trivial metadata tracking.

As there’s only one nominated writer for the quorum of nodes, the writer knows which nodes in the quorum have accepted writes up to what version. This means that reads don’t need to be quorum reads, the primary is free to send read requests only to one of the at-least-four nodes that it knows should have the correct data. Read replicas use the same storage nodes as the primary, but follow with a ~20ms lag to only read up to the Volume Durable LSN. Read-only replicas consume the binlog from the primary, and apply to cached pages only. Uncached data comes from storage groups. S3 is used for backups.

There’s a recovery flow to follow when the primary fails. A new primary must contact every storage group to find what’s the highest LSN below which all log records are known, and then recover to min(max LSN per group), but again, that’s a summary, because the reality seems complicated. However, the work of then applying the redo logs to properly recover to that LSN is now parallelized across many storage nodes, leading to a faster recovery.

Discussion

- Is this a trade of decreasing the amount of work on writes at the cost of increasing the amount of work on reads?

-

Moving the storage to over the network does add some cost, reconstructing full pages at arbitrary versions isn’t cheap, and while MySQL could apply the WAL entry directly to the buffer cached page the storage node might have to fetch the old page from disk. But much of the work is work that MySQL would otherwise be doing: finding old versions of tuples by chaining through the undo log, fuzzy checkpointing, etc. So while fetching pages from disk over a network is slower than fetching them locally, it is a good argument that it lets MySQL focus more on the query execution and transaction processing than storage management.

Aurora Multi-Master

Aurora Multi-Master was made generally available in August of 2019 and was deprecated in 2023. Though there’s no publications about how Aurora Multi-Master worked, there was an AWS Re:Invent talk and an HPTS talk which gave some details on its internals.

The major design decision referenced in other multi-master papers is that conflicts between the multiple masters were resolved optimistically at commit time.

Aurora Serverless

Bradley Barnhart, Marc Brooker, Daniil Chinenkov, Tony Hooper, Jihoun Im, Prakash Chandra Jha, Tim Kraska, Ashok Kurakula, Alexey Kuznetsov, Grant McAlister, Arjun Muthukrishnan, Aravinthan Narayanan, Douglas Terry, Bhuvan Urgaonkar, and Jiaming Yan. 2024. Resource Management in Aurora Serverless. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 17, 12 (August 2024), 4038–4050. [scholar]

This paper describes the transition from their naive Aurora Serverless v1 (ASv1) to Aurora Serverless v2 (ASv2). It covers both the product dimensions of billing and end-user experiences, and the internal technical parts of how to orchestrate scaling up/down, managing load, and transferring user workloads with minimum distruption. ASv1 relied upon relaunching a database instance in order to change its scale. A multi-tenant proxy frontend was created to allow sessions to be transferred between a rapidly restarted database instance. This session transfer was incomplete (temporary tables couldn’t be transferred), disruptive (due to transient unavailability), and inelastic as paying the cost of a restart only made sense for large (power of 2) instance size changes. The goal of ASv2 was to be able to scale faster, less disruptively, and be able to better track a cyclical workload.

Customers buy Aurora Serverless in units of Aurora Capacity Units (ACUs), which is a combination of 2GB RAM + 0.25 vCPU + an undefined amount of networking and block device throughput. Users define a ceiling and floor in ACU of what they wish for their database to scale up or down to, and then Aurora Serverless tries to autoscale to approximate fully elastic, usage-driven pricing.

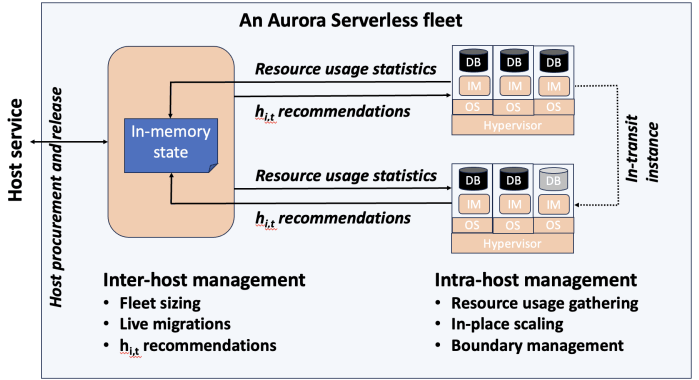

Aurora Serverless is split into fleet-wide, inter-host rebalancing; and host-local, intra-host, in-place scaling.

Instance Managers gather resource usage information for database instances on a host, and work within the host’s resource limits to scale instances up or down to meet the resource needs. The Fleet Manager controls database instance to host assignment. Hosts' resources are oversubscribed, and when hosts are under resource pressure (at a critical level for CPU, allocated RAM, network, or disk throughput), the Fleet Manager will assign temporary ACU limits and live migrate database instances to redistribute heat across the cluster and relieve the resource pressure. The scale-up rate is limited by the Instance Manager to give the Fleet Manager time to react. The Fleet Manager will not live migrate from hosts which are deemed not to have the available network bandwidth to sustain an out-migration. New database instances are placed assuming minimum ACU usage. The Fleet Manager also adjusts the size of the fleet according to predicted and actual demand.

The Fleet Manager must choose what instance to move, and to which host to move it. Choosing an instance is a three step process: remove any ineligible instances, compute a preferences score (e.g. don’t move frequently moved instances, prefer instances that have ack’d a heartbeat recently), and compute a numerical score (how much resources will be freed up, combined with what fraction of unused resources does this instance have). Instances with equal preference scores are tiebroken by numerical score. Target host selection proceeds similarly: ineligible hosts are removed, compute a preference score (fault tolerance distribution, no recent migration failures), and a numerical score (best-fit binpacking score, and most utilized resource percentage). In the evaluation, they show that this 3 phase approach does a better job of distributing load across the fleet than a baseline of just best-fit with less instance movement.

Database instances are wrapped in VMs for security reasons, and thus resource elasticity must be done in cooperation with the guest OS of each VM. Every VM is of the same 128 ACU maximum instance size. This relies on Nitro’s SR-IOV support for having efficient virtualized IO. Memory elasticity required a number of changes: memory can be offlined to prevent it from being used for page cache and so that Linux doesn’t keep a page table entry around for every page, cold pages are swapped out, and 4KB pages are coalesced to make 2MB sized free pages which can be reclaimed by the hypervisor. Memory scales up based on the desired buffer pool size over the past 30 seconds, and down over the past 60 seconds. CPU scales up based on P50 over the past 30 seconds, and down by P70 over the past 60 seconds. Scaling up is done using the maximum of the two, scaling down uses the minimum.

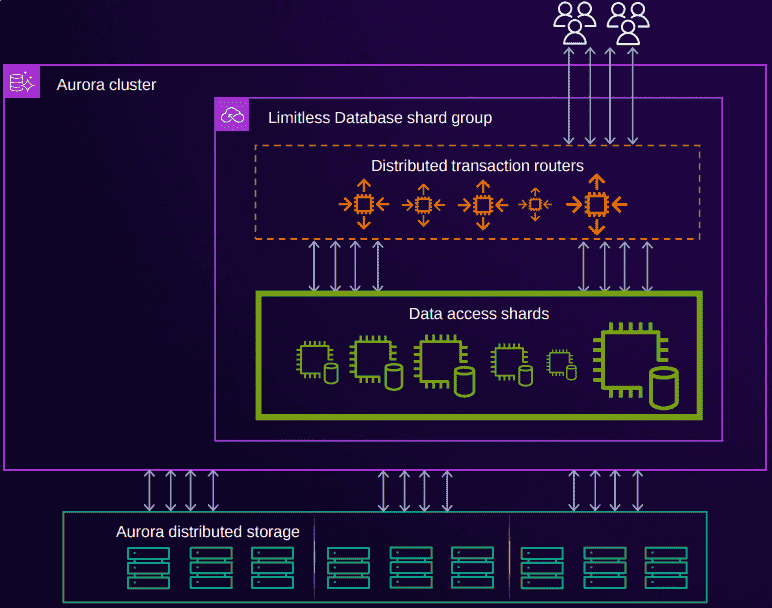

Aurora Limitless

Aurora Limitless reuses the "Aurora" brand, but is much more similar to a shared-nothing distributed database like Spanner than it is to the Aurora database we’ve been discussing thus far. If you’re interested in learning about Limitless anyway, the only released information on it has been as part of AWS Re:Invent talks.

Microsoft

Socrates ★

Panagiotis Antonopoulos, Alex Budovski, Cristian Diaconu, Alejandro Hernandez Saenz, Jack Hu, Hanuma Kodavalla, Donald Kossmann, Sandeep Lingam, Umar Farooq Minhas, Naveen Prakash, Vijendra Purohit, Hugh Qu, Chaitanya Sreenivas Ravella, Krystyna Reisteter, Sheetal Shrotri, Dixin Tang, and Vikram Wakade. 2019. Socrates: The New SQL Server in the Cloud. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD/PODS '19), ACM. [scholar]

The paper spends some time talking about the previous DR architecture, its relevant behavior and features, and its shared nothing design. There’s also a decent amount of discussion around about adapting a pre-existing RDBMS to the new architecture. It’s overall a very realistic discussion of making major architectural changes to a large, pre-existing product, but I’m not going to focus on either as this is only a disaggregated OLTP overview.

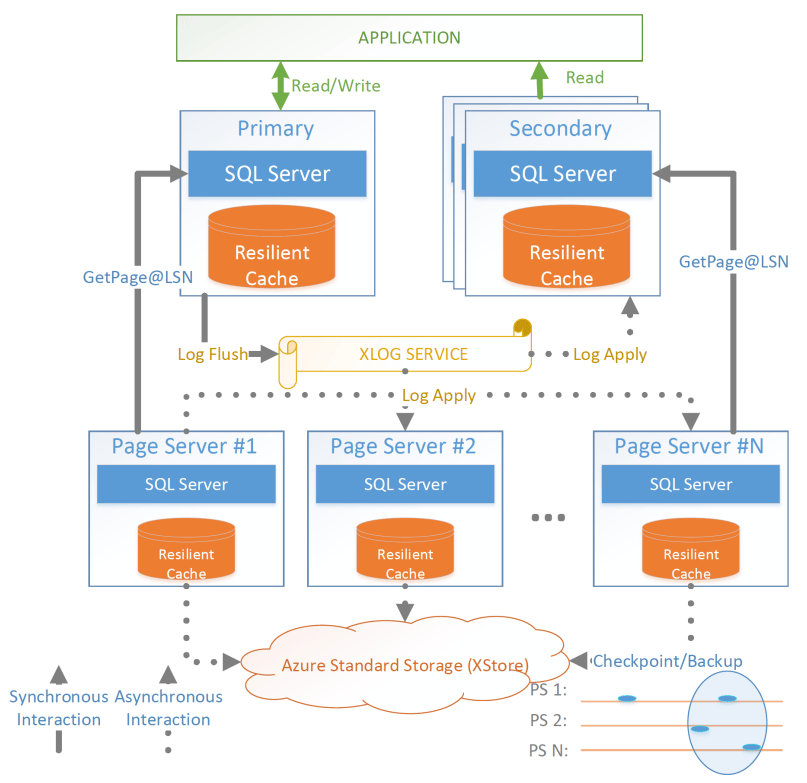

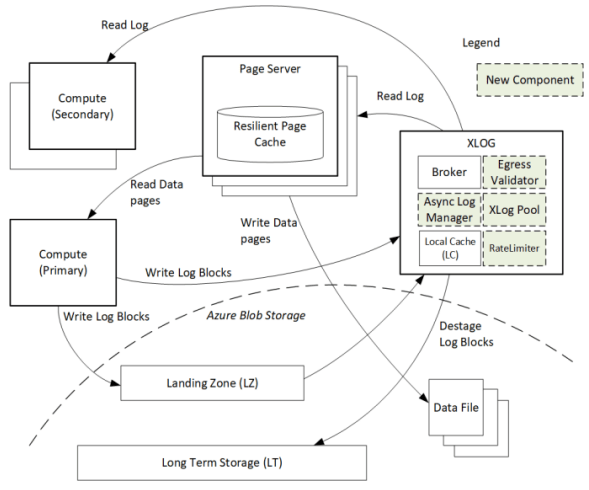

The architecture of Socrates separates durability (implemented by the log) from availability (implemented by the storage tier). Durability does not require copies of data in fast storage. Availability does not require a fixed number of replicas. Separating the two concepts allows Socrates to use cheap HDDs for durability, and fewer fast and expensive SSDs for storage tier availability.

Their major design decisions are:

-

All processes have a local disk-based cache. (More on this below.)

-

Azure Premium Storage is used as a LandingZone (LZ) for the WAL, due to its low latency and high durability.

-

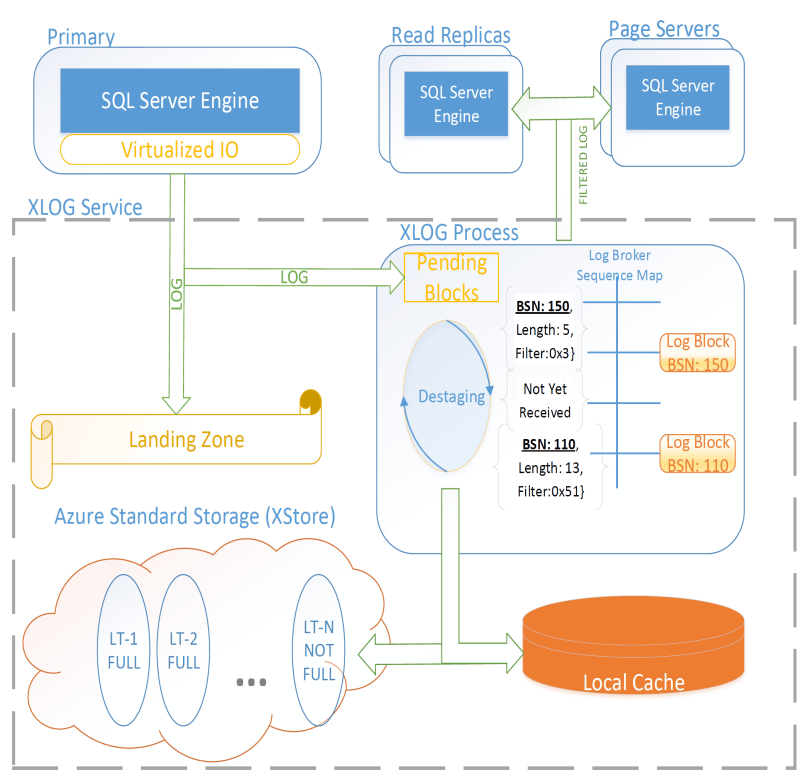

A router XLOG process for availability of WAL entries and for dissemination to page servers.

-

XStore is long term storage for log blocks, and is Azure standard storage.

A primary compute node is nearly unaware that it is the primary of a disaggregated database, and also isn’t aware of any secondary read replicas. It only performs its core function: executing transactions to produce write-ahead log entries. All other responsibilities are offloaded. Writes into the Landing Zone are done via a virtualized filesystem, and a from-storage recoverable buffer pool is integrated in just about I/O virtualization. All of checkpointing, backup/restore, page repair, etc. are delegated to lower storage tiers.

To minimize impact from failures, compute nodes extend their buffer pool to disk by representing it as a table in Hekaton, an in-memory storage engine. A buffer pool on SSD would normally seem like it defeats the point, but otherwise a cold start means dumping gigabytes worth of page fetches at Page Servers, with terrible performance until the working set is back in cache.

A key part of Socrates is its separate XLOG service which is responsible for the WAL. The primary sends log to LZ and XLOG in parallel. XLOG buffers received WAL segments until the primary informs it the segments are durable in the LZ, at which point they’re forwarded onto the page servers. It also has a local cache, and moves log segments to blob storage over time. (And note that this is a major difference from Aurora — Aurora partitions the WAL across page servers, whereas Socrates has a centralized WAL service.)

Page servers don’t store all pages. They have a large (and persistent) cache, but some pages live only on XStore.

Page servers exist largely to serve the single GetPage@LSN RPC, which serves the page at a version that’s at least the specified LSN.

Thus, they aren’t required to materialize pages at any arbitrary version, and can keep only the most recent. For checkpointing, Page Servers regularly ship modified pages to XStore.

B-tree traversals from replicas sometimes need to restart if a leaf page is a newer LSN than the parent.

The Socrates team is working on offloading bulk loading, index creation, DB reorgs, deep page repair, and table scans to Page Servers as well.

Backup and restore uses XStore’s Point-In-Time-Restore operation to save periodic snapshots of page data. Restore identifies the snapshots taken before the restore, and the log range needed to bring the snapshots up to the requested point in time. These are then copied to new blobs and each blob is attached to a new Page Server instance, with a new SLOG process bootstrapped on the copied log to facilitate applying the changs to the requested restore time.

Discussion

Socrates feels like a very modern object storage-based database in the WarpStream or turbopuffer kind of way for it being a 2019 paper. The extended buffer pool / "Resilient Cache" on the primary sounds like a really complicated mmap() implementation.

- Would VM migration keep the cache?

-

Probably not? This raised an interesting point that trying to binpack SQL Server instances across a fleet of instances seems difficult, especially with them all being tied to a persistent cache. Azure SQL Database is sold in vCPU and DTU models, which seem to be more reservation based, so maybe there isn’t an overly high degree of churn?

- Are the caches actually local SSD or are they Azure Managed Disks?

-

Consensus was that it seemed pretty strongly implied that they were actually SSD.

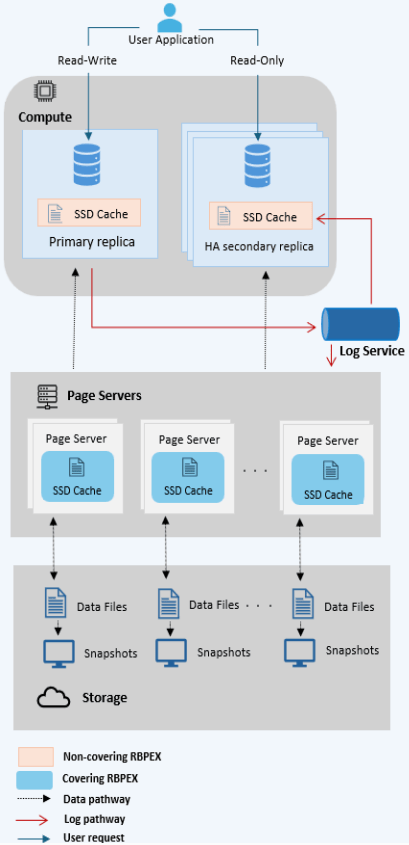

Hyperscale RBPEX

Rogerio Ramos, Prashanth Purnananda, Hanuma Kodavalla, Chaitanya Gottipati, Harshil Ambagade, Ankit Anvesh, and Srikanth Sampath. 2025. Hyperscale Resilient Buffer Pool Extension in Azure SQL Database. In 2025 IEEE 41st International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), IEEE, 4222–4233. [scholar]

Years after Socrates has been placed into production under the brand name Azure SQL Database Hyperscale, Microsoft folk have returned with a deep dive on their Resilient Buffer Pool Extension (RBPEX), which extended the in-memory buffer pool to store pages on SSD in order to minimize the performance impact of process restarts. Traditionally, a buffer pool is only in memory, as is caching page reads from SSD. In Hyperscale, the buffer pool is on memory and local SSD, and is used to cache page reads from remote page servers. The same RBPEX is used on page servers as the local storage of pages held on object storage. On the compute node, it’s an incomplete cache: a non-covering RBPEX. On the page servers, what is in "cache" is an exact mirror of the pages in object store: a covering RBPEX.

The RBPEX File is the backing store for data pages cached in RBPEX. It is a local file, sized as a multiple of SQL Server’s page size (8KB), broken into 1MB sized segments, and stores no extra metadata other than page contents. All metadata is instead tracked as SQL tables using Hekaton, SQL Server’s in-memory engine. The hash-based table PageTable maps a <DbId, FileId, PageId> tuple to its <Offset, Timestamp, State> information. Offset stores the offset in the RBPEX File, Timestamp stores when the page was last written to or read from the RBPEX, and State stores one of the states {Valid, Invalid, InFlight}. Valid pages are those where the RBPEX File has the exact same copy of the data as the underlying data file being cached. An InFlight page is one where a write operation is ongoing and the RBPEX File contents may be stale. At recovery time, the PageTable is scanned, and all rows with InFlight and Invalid statuses are removed. An RbpexMetadataTable persists metadata about the RBPEX File itself.

SQL Server has an I/O abstraction layer called the File Control Block (FCB), which allows reads and writes to be re-routed through RBPEX’s FCB for caching only within Hyperscale. When a page is to be read into memory, the RBPEX FCB intercepts the page read and serves it out of the RBPEX File if the PageTable says that there’s a Valid page for the given PageId. If not, the read goes to the underlying data file (which on the primary node turns into a Page Server GetPage@LSN RPC). Statistics are tracked on page accesses so that a background thread can move frequently written pages into the RBPEX. The entire point of the RBPEX is to reduce cold start times, so it’s important to ensure frequently read but rarely written pages still make it into the RBPEX. There’s also a number of hints supported to avoid bringing writes from bulk data loads or reads from large analytical table scans into the RBPEX, as doing so would evict more useful pages to have in cache.

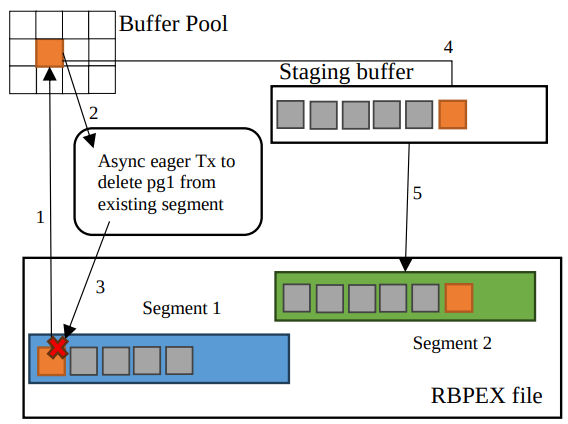

For page writes, one would expect the flow to be: mark page as InFlight, write page to RBPEX and underlying data file concurrently, and mark page as Valid again. However, this would require many small updates to the PageTable, imposing notable overhead, and would be many random I/O requests. Instead, when a page is first marked dirty in the buffer pool, it is asynchronously deleted from the PageTable. When dirty page writeback is initiated, the RBPEX FCB buffers the dirty page writes by placing them into a staging buffer. (Reads can still be served out of the staging buffer.) The staging buffer is flushed to the RBPEX File in full 1MB segments at a time. When the pages are flushed from the staging buffer, they are inserted into the PageTable as InFlight. After the whole segment is durable, all pages are updated to Valid. This flow of asynchronous deletes and inserts is better than updating a row, as deletes can be batched and inserts can also be lazily made durable. In the worst case, missing an insert to the PageTable on recovery just means the page won’t be seen as in the cache even though it’s on disk.

Secondaries can have their cache primed to minimize the performance impact of a failover by prefetching hot pages in the database. The primary tracks hot pages, and periodically pushes a sample of page hit counts to the Page Servers. Secondaries can then query the Page Servers to know which pages to fetch to pre-warm their cache.

A background trimmer thread handles cold page and eviction tasks. The timestamp of last access is maintained per segment in memory, and the least recently used segment has all of its pages evicted. Segments with low occupancy, due to updates marking the old page as Invalid, are also released and their pages evicted.

The Covering RBPEX on Page Servers is organized into 16MB segments of contiguous pages of the database. A Covering RBPEX stores its metadata in a separate SegmentTable, as per-page information doesn’t need to be tracked. At startup, all data pages associated with the Page Server are loaded from object storage and inserted into the RBPEX. Updates are then pulled from the XLOG and applied, and then the Page Server is ready to serve pages. Page updates work similarly to what is described above, except a DirtyPageBitmap tracks which pages have been updated in a given segment. A Page Server can also evict cold segments, and Azure SQL metrics show ~40% of all segments as not having been accessed in the last 7 days.

The evaluation shows a 600us local RBPEX read latency and a 1000us Page Server read latency, though they later state RBPEX reads on compute nodes are 200us. Their graphs for recovery performance show cache hit rate, remote page read QPS and page latch wait time, but not overall system QPS as I’d expect, but it takes about 12 seconds for a cold cache to be filled.

Hyperscale XLOG

Jack Hu, Eric Lee, Prashanth Purnananda, and Hanuma Kodavalla. 2025. Scaling and Hardening XLOG: The SQL Azure Hyperscale Log Service. In 2025 IEEE 41st International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), IEEE, 4211–4221. [scholar]

From the initial implementation described in the Socrates paper, there have been three major areas of improvements: moving from request processing from blocking to non-blocking, improving IO coalescing and caching for groups of older readers, and the addition of layers of checksum validation.

When Page Servers issued a GetLogBlocks request to XLOG and the page server was already fully caught up, XLOG would wait until there was another piece of log data before replying to the request, transforming it into a long polling request. This request processing was done synchronously, including the waiting, which would then block a request request handling thread. Once the number of Page Servers exceeded the number of threads, this turned into incredibly poor latency and performance as new requests would be starved. The solution was to change to an asynchronous, non-blocking model for processing requests. The paper gives this topic a full treatment, but the problem and solution are no different than any other RPC-based or backend service handling long-running RPCs or doing blocking work on a threadpool.

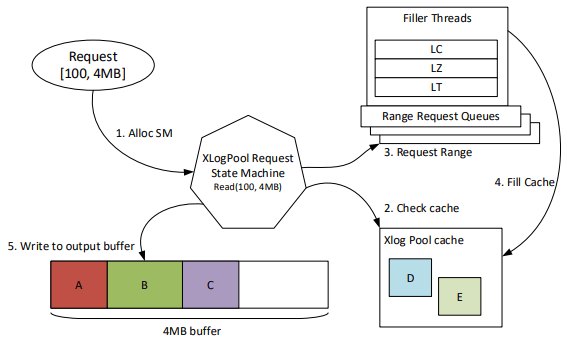

Rack outages, system upgrades, or restoring from backups all caused a large number of Page Servers to appear which requested log data that would no longer be in XLOG’s local cache. XLOG would handle these requests all independently, issuing a read for potentially overlapping data from Azure Storage. This wave of reads would then trigger throttling in Azure Storage, severely penalizing the XLOG and affecting all requests to the Landing Zone. The fix to this was twofold. First, a rate limiter was built into XLOG itself to keep to 190MB/s of reads, and not cross the 200MB/s limit that causes Azure Storage to drastically penalize it. (The evaluation makes this look like exceeding 200MB/s meant 100MB/s would be enforced.) Second, a separate cache was added for recently fetched log blocks from Azure Storage and a data structure maintained in memory with the ranges for all outstanding requests. New requests would then have their ranges be deduplicated against existing requests. Dedicated filler threads would fetch desired ranges into the XLOG Pool Cache, and then requests blocked on those ranges would consume the data. Coalescing these requests also meant more new log block could be fetched from Azure Storage, as the bandwidth wasn’t being wasted re-fetching the same block repeatedly from concurrent requests.

A high corruption rate associated with a specific model of SSDs by a "well-known vendor" seemed to drive a number of improvements on data integrity checking within Hyperscale. Egress Validation was added, which kept a small hashmap in memory on XLOG of Block Sequence Number to hash of block. The first time a block was served to a client, the hash would be stored, and subsequent requests would validate that the calculated hash matched what had been stored in the hashmap for the same BSN. Any differing result implied a corruption. End-to-end checksum validation was also added. Compute nodes stamp each block with a checksum, which is validated when first read by XLOG, before being served by the XLOG, and again upon being received by the Page Server. Code manipulating log blocks was changed to use overflow-detecting integer math libraries to ensure interpreting the block headers on corrupted blocks would not lead to crashes. Together, these changes provided more assurance that critical data remained intact.

The evaluation showed the impact of each change. The impact was already well alluded to by the descriptions earlier in the paper, so nothing felt surprising. The combination of the async request processing and XLOG Pool changes permitted significantly better throughput of log blocks as page server count increased, which was exactly the goal of the work.

Alibaba

As broad context, Alibaba is really about spending money on fancy hardware. I had talked about this a bit in Modern Database Hardware, but Alibaba’s papers quickly illustrate that they’re more than happy to solve difficult software problems by spending significant stacks of money on very modern hardware. Notably, Alibaba has RDMA deployed out internally, seemingly to the same extent that Microsoft does, except Microsoft seems to keep a fallback-to-TCP option for most of their stack, and Alibaba seems comfortable building services that critically depend on RDMA’s primitives.

PolarFS

Wei Cao, Zhenjun Liu, Peng Wang, Sen Chen, Caifeng Zhu, Song Zheng, Yuhui Wang, and Guoqing Ma. 2018. PolarFS: an ultra-low latency and failure resilient distributed file system for shared storage cloud database. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 11, 12 (August 2018), 1849–1862. [scholar]

Alibaba took an unusual first step in building a disaggregated OLTP database. Instead of spending their effort building a separate pageserver and modifying the database to request pages from it and offload recovery to it, they invested effort into just building a sufficiently fast distributed filesystem. A year after the paper was published, Alibaba opensourced PolarFS as AsparaDB/PolarDB-FileSystem (and PolarDB as ApsaraDB/PolarDB-for-PostgreSQL

, with the PolarFS usage included), and so I’ve sprinkled links to it in the summary.

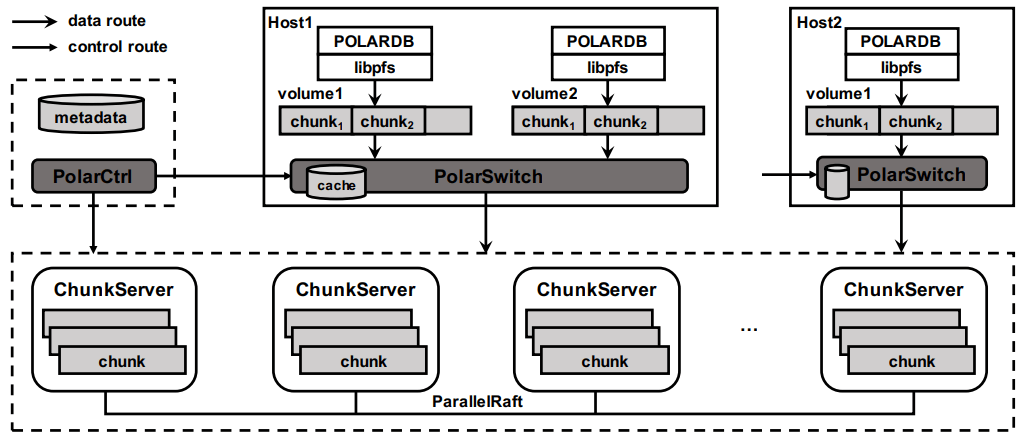

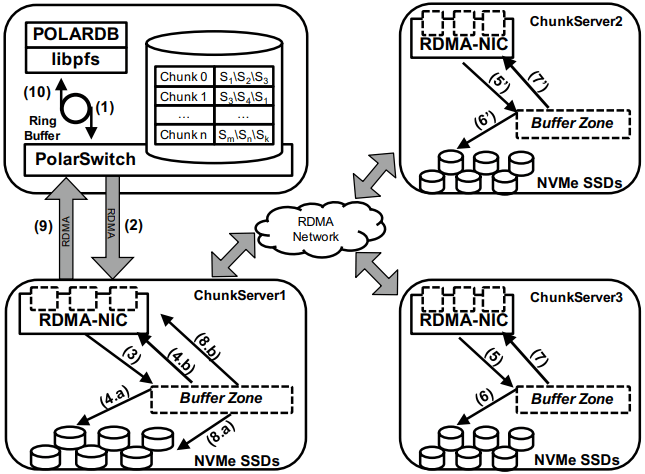

In terms of architectural components: libpfs is the client library that exposes a POSIX-like filesystem API, PolarSwitch is a process run on the same host which redirects I/O requests from applications to ChunkServers, ChunkServers are deployed on storage nodes to serve I/O requests, and PolarCtrl is the control plane. PolarCtrl’s metadata about the system is stored in a MySQL instance. The only necessary modifications to PolarDB were to port the filesystem calls to libpfs.

The libpfs API is given as:

int pfs_mount(const char *volname, int host_id)

int pfs_umount(const char *volname)

int pfs_mount_growfs(const char *volname)

int pfs_creat(const char *volpath, mode_t mode)

int pfs_open(const char *volpath, int flags, mode_t mode)

int pfs_close(int fd)

ssize_t pfs_read(int fd, void *buf, size_t len)

ssize_t pfs_write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t len)

off_t pfs_lseek(int fd, off_t offset, int whence)

ssize_t pfs_pread(int fd, void *buf, size_t len, off_t offset)

ssize_t pfs_pwrite(int fd, const void *buf, size_t len, off_t offset)

int pfs_stat(const char *volpath, struct stat *buf)

int pfs_fstat(int fd, struct stat *buf)

int pfs_posix_fallocate(int fd, off_t offset, off_t len)

int pfs_unlink(const char *volpath)

int pfs_rename(const char *oldvolpath, const char *newvolpath)

int pfs_truncate(const char *volpath, off_t len)

int pfs_ftruncate(int fd, off_t len)

int pfs_access(const char *volpath, int amode)

int pfs_mkdir(const char *volpath, mode_t mode)

DIR* pfs_opendir(const char *volpath)

struct dirent *pfs_readdir(DIR *dir)

int pfs_readdir_r(DIR *dir, struct dirent *entry,

struct dirent **result)

int pfs_closedir(DIR *dir)

int pfs_rmdir(const char *volpath)

int pfs_chdir(const char *volpath)

int pfs_getcwd(char *buf)Which has a few interesting subtleties, and you see this API in the OSS repo in pfsd_sdk.h. The VFS layer implemented for Postgres is in polar_fd.h, which is a slight superset of the API given in pfsd_sdk.h. I’m assuming the lack of a pfs_fsync() means all pfs_pwrite()s are immediately durable, and though pfsd_fsync() exists in pfsd_sdk.h, it has a comment of /* mock */ over it. Postgres is a known user of sync_file_range(), which I’m assuming is equally no-op’d. Volumes are mounted, and are dynamically growable or shrinkable, but most filesystems generally aren’t incredibly compatible with being dynamically resized. There is both direct IO and buffered IO support, even though the API doesn’t indicate it.

The given API describes PolarFS’s file system layer which maps directories and files down onto blocks within the mounted volume. The contents of a directory or the blocks associated with a file are written as blocks, with a root block holding the root directory’s metadata. To transactionally update a set of blocks (so that read replicas see a consistent filesystem), there is a journal file which serves as a WAL for file system updates, and libpfs implements disk paxos to coordinate between replicas who is allowed to write into the journal.

The storage layer provides interfaces to manage and access volumes for the file system layer. A volume is divided into 10GB chunks, which are distributed across ChunkServers. The large chunk size was chosen to minimize metadata overhead so that it’s practical to maintain the entire chunk-to-server mapping in memory in PolarCtrl. Each ChunkServer manages ~10TB of chunks, so this still offers a reasonable ratio for practical load balancing on ChunkServers. Within a ChunkServer, each chunk is divided into 64KB blocks which are allocated and mapped on demand. Each chunk is thus 640KB of metadata to track chunk LBA to block location, or 640MB for all 1000 chunks per server.

PolarSwitch is a daemon that runs alongside any application using libpfs. Libpfs forwards IO requests over a shared memory ring buffer to PolarSwitch, and PolarSwitch then divides the IO requests into per-chunk requests, references its in-memory mapping of chunk-to-server and sends out the requests. Completions are reported via another shared ring buffer (similar to io_uring). The reasoning for maintaining this as a separate daemon isn’t given, but I’m assuming it was forced as utilizing RDMA as the network transport means that either only one process can use the NIC, or in the case of vNICs, a fixed number of processes that’s less than the number of instances per host they wish to run.

ChunkServers run on the disaggregated storage servers, with one ChunkServer per SSD on a dedicated CPU core. (Which implies they have SSDs which are at least 10TB is size?) Each chunk contains a WAL which is kept on a 3D XPoint SSD (aka Intel Optane). Replication across ChunkServers is done using ParallelRaft, a Raft variant optimized to permit out-of-order completions. SPDK is used to maximize IOPS per core, and is why each ChunkServer gets a dedicated core so that it may poll infinitely. Likely due to the large chunk and total data size, ChunkServers are given a reasonably high tolerance for being offline.

PolarCtrl is the control plane deployed on a dedicated set of machines. It manages membership and liveness for ChunkServers, maintaining volume and chunk-to-server mappings, assigning of chunks to ChunkServers, and distributing metadata to PolarSwitch instances.

Raft serializes all operations to a log, and commits them in-order only. This causes write requests serialized later in the log to wait for all previous writes to be committed before their own response can be sent out. This caused throughput to drop by half as write concurrency was raised from 8 to 32. As a result, Raft was altered to allow out-of-order acknowledgements from replies and commit responses back to clients, and to permit holes in the Raft log. They detail the effect that this had on leader election and replica catchup. This novel variant effectively transforms Raft into generalized multi-paxos, and no explanation was given as to why they didn’t just implement that directly rather than adapting Raft into it.

Disk snapshots are supported by PolarFS by PolarSwitch tagging requests with a snapshot tag on subsequent requests to ChunkServers. On receiving a new snapshot tag, ChunkServers will snapshot by copying their LBA-to-block-location mapping, and will modify those blocks in a copy-on-write fashion afterwards. After a ChunkServer reports having taken the snapshot, PolarSwitch stops adding the snapshot tag to requests to that ChunkServer.

The evaulation section shows that PolarFS adds minimal overhead as compared to a local ext4 volume, and with latency ~10x lower than Ceph and 2x higher throughput. Just to review, it achieved those results by packing extra large SSDs (>10TB), Intel Optane, RDMA, and large amounts of RAM, each of which is individually expensive, all into one deployment cluster, and special cased an infrastructure stack for it. Not cheap, nor (given everything I’ve heard about using SPDK and RDMA) easy to write, deploy, or maintain.

PolarDB Computational Storage

Wei Cao, Yang Liu, Zhushi Cheng, Ning Zheng, Wei Li, Wenjie Wu, Linqiang Ouyang, Peng Wang, Yijing Wang, Ray Kuan, Zhenjun Liu, Feng Zhu, and Tong Zhang. 2020. POLARDB Meets Computational Storage: Efficiently Support Analytical Workloads in Cloud-Native Relational Database. In 18th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 20), USENIX Association, Santa Clara, CA, 29–41. [scholar]

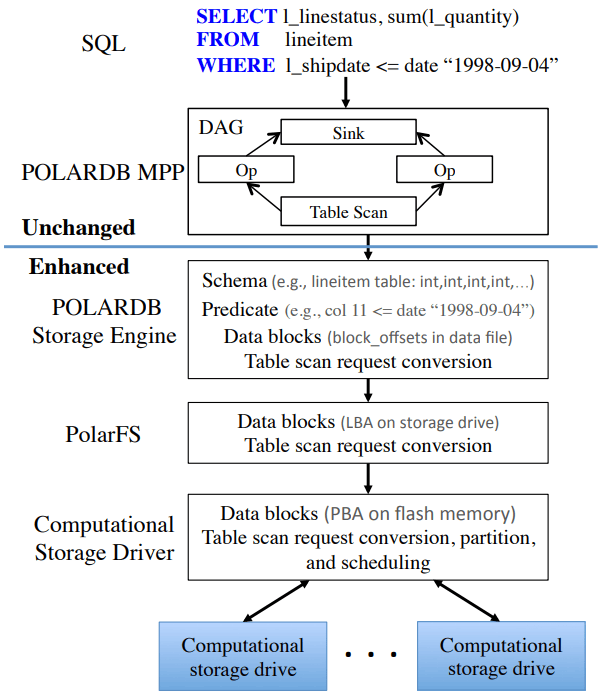

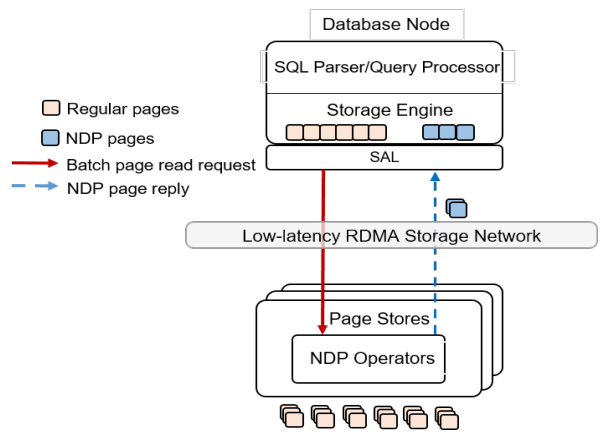

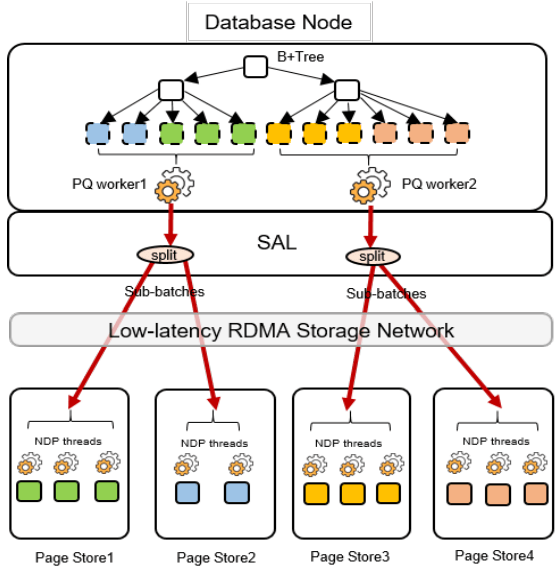

This paper is more focused on the computational storage side of integrating SmartSSDs (in the form of ScaleFlux’s product) into a database, and the database they happen to have chosen for this work is a disaggregated one. However, I’ve included it in this listing because it’s the only paper that gets into the topic of tight integration between page servers and compute for pushdown in detail. I’ll be doing a disservice to the actual paper in this summary, and focusing only on the pushdown aspect.

The draw of pushdown in a disaggregated architecture is to minimize the amount of processing done on non-matching data. Pushing table scan filters from compute nodes to storage nodes reduces the number of rows or pages that the storage nodes must send over the network. With computational storage, those filters can be pushed all the way to the SSD itself, removing the need to even send non-matching rows over the PCIe bus. However, it is moving compute work from the compute node to storage, and compute resources are much more limited in storage. Rather than scale up the compute resources of the storage nodes, Alibaba elected to increase the compute of the storage devices themselves by utilizing SSDs with on-board FPGAs.

The required changes in PolarDB start at the scan operator. PolarDB read data from files by requesting blocks by their offset within the file. That has been enhanced to include schema of the table and the preciate to apply to the block request. The ChunkServers split the predicates into those that can be pushed to the FPGA, and those that need to be evaluated on the CPU. In the PolarFS paper, ChunkServers are described as having a one-to-one relationship with an attached 10TB SSD and tracking 64KB sized blocks. In this paper, ChunkServers stripe data across a number of SmartSSDs with 4MB stripes, and 4KB blocks are snappy compressed and thus variable length. ChunkServers split the request into one per stripe, and forward them to the corresponding SmartSSDs.

The computational storage device has a corresponding driver in Linux which exposes it as a block device.[1] The ChunkServer sends the driver the scan request. The driver reorders filters to match the hardware’s pipelined table record decoding and translates logical blocks to physical blocks on the NAND flash memory. The driver also splits larger scans into smaller ones to avoid head-of-line blocking causing high latency for concurrent requests. [1]: See NVMe Computational Storage Standardization if you’d like more of a view into how SmartSSD<->Host integration works.

PolarDB was modified to be more accomodating to efficient, simple evaluation of predicates. The encoding format for keys and values were changed to always be memcmp()-orderable, so that the FPGA wouldn’t need to understand different value encoding formats and comparisons for them. Blocks were also changed from having a footer with metadata to a header with metadata, so that decoding of the block could happen as it’s being read.

Their evaluation compares no pushdown, CPU-only pushdown, and computational storage (CSD) pushdown on TPC-H. Query latency for uncompressed CPU-based pushdown and CSD-based pushdown look like very similar 2-3x improvementes, which is unsurprising as it reflects that the majority of the gain is from freeing the one compute instance from receiving data, evaluating the filter, and then throwing it away. With compressed data, the CSD-based pushdown is a bit noticably better, as decompression isn’t free, but can be done efficiently in hardware. The PCIe and Network Traffic graphs per query show that each layer of pushdown removes another 2-3x of network traffic (CPU-based pushdown) or PCIe traffic (CSD-based pushdown).

PolarDB Serverless ★

Wei Cao, Yingqiang Zhang, Xinjun Yang, Feifei Li, Sheng Wang, Qingda Hu, Xuntao Cheng, Zongzhi Chen, Zhenjun Liu, Jing Fang, Bo Wang, Yuhui Wang, Haiqing Sun, Ze Yang, Zhushi Cheng, Sen Chen, Jian Wu, Wei Hu, Jianwei Zhao, Yusong Gao, Songlu Cai, Yunyang Zhang, and Jiawang Tong. 2021. PolarDB Serverless: A Cloud Native Database for Disaggregated Data Centers. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD/PODS '21), ACM, 2477–2489. [scholar]

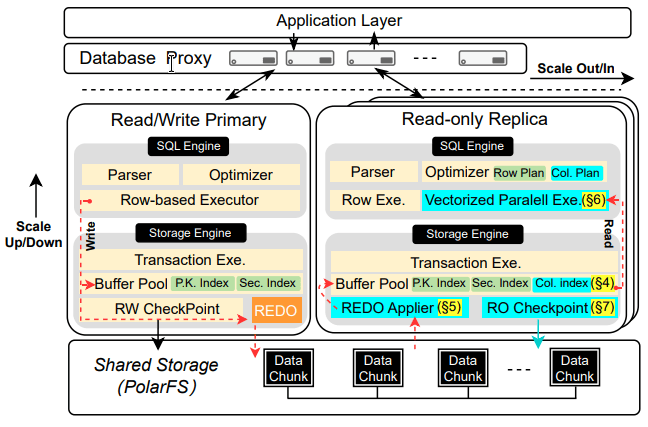

The PolarDB Serverless paper is about leveraging a multi-tenant scale-out memory pool, built via RDMA. This makes them also a disaggregated memory database! As a direct consequence, memory and CPU can be scaled independently, and the evaluation shows elastically changing the amount of memory allocated to a PolarDB tenant.

However, implementing a page cache over RDMA isn’t trivial, and a solid portion of the paper is spent talking about the exact details of managing latches on remote memory pages and navigating b-tree traversals. Specifically, B-tree operations which change the structure of the tree required significant care. Recovery also has to deal with that the remote buffer cache has all the partial execution state from the failed RW node, so the new RW node has to release latches in the shared memory pool and throw away pages which were partially modified. I’ll be eliding all the RDMA-specific details, and just covering the parts that would equally apply to a slower, TCP-based memory disaggregation architecture as well. There’s also a lot packed into this paper, as it covers PolarDB and PolarFS enhancements as well, so be warned.

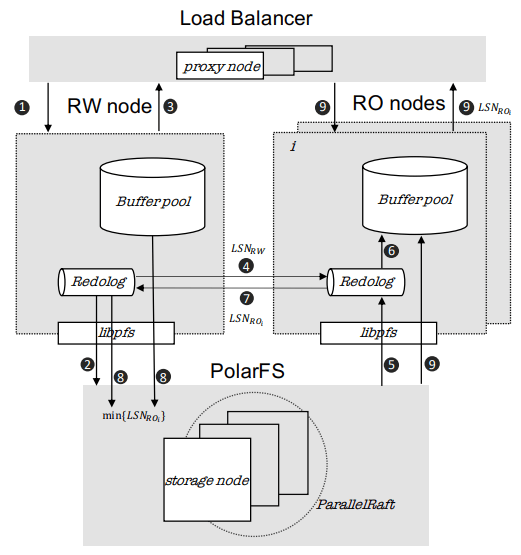

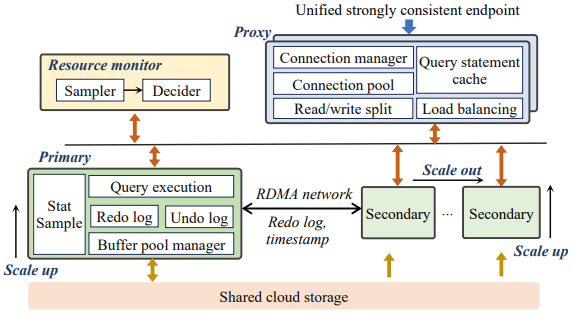

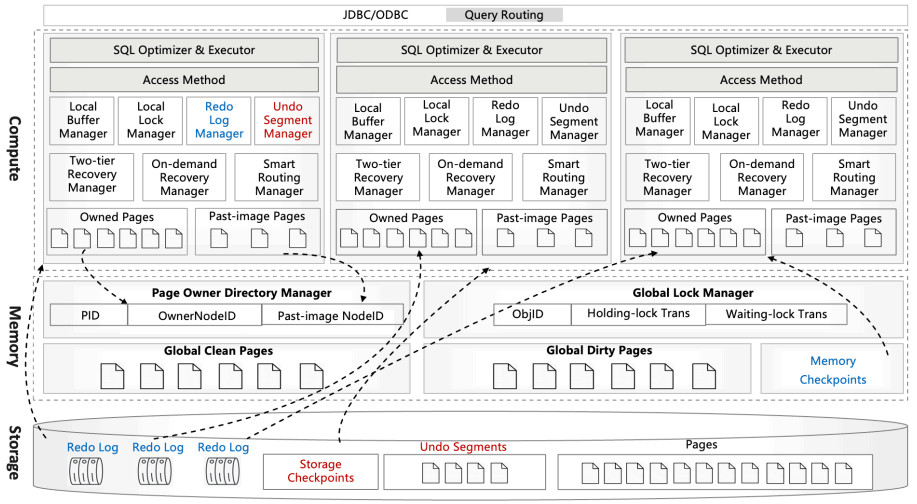

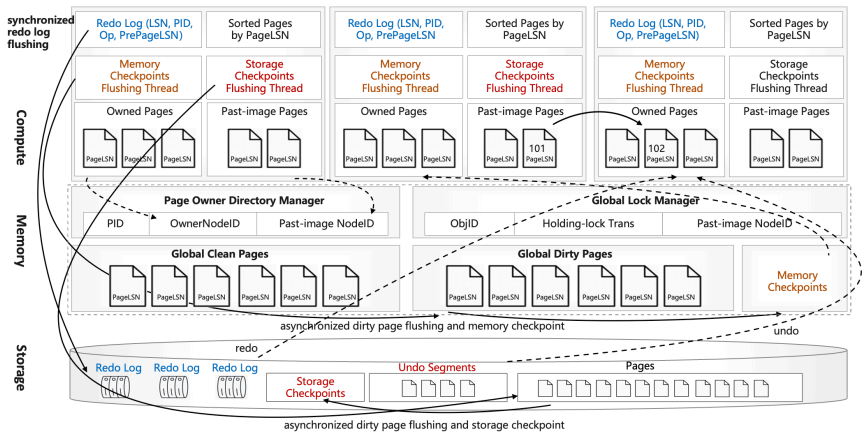

They offer an architecture diagram for PolarDB as a whole:

However, there’s a few things I think it doesn’t represent well:

-

PolarFS was extended to support separate log chunks and page chunks. The WAL is committed into log chunks, and they directly state the design is closer to the Socrates XLOG than Aurora.

-

Due to the use of ParallelRaft, logs are sent only to the leader node of the page chunk, who will materialize pages and propagate updates to other replicas.

-

There’s also a timestamp service which, which uses RDMA to quickly and cheaply serve timestamps that’s not included in the diagram.

PolarDB Serverless extends this to add a remote memory pool, which allows read-only and read-write to share the same buffer pool. Remote memory access is performed via librmem, which exposes the API:

int page_register(PageID page_id,

const Address local_addr,

Address& remote_addr,

Address& pl_addr,

bool& exists);

int page_unregister(PageID page_id);

int page_read(const Address local_addr,

const Address remote_addr);

int page_write(const Address local_addr,

const Address remote_addr);

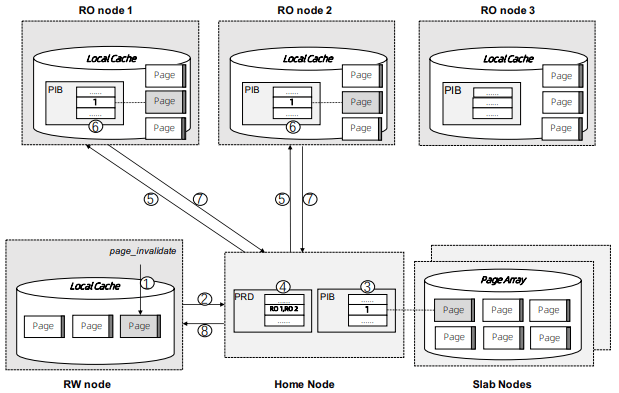

int page_invalidate(PageID page_id);The minimum unit of allocation is a 1GB physically contiguous slab, which is divided into 16KB pages (because PolarDB is MySQL, and MySQL uses 16KB pages). A slab node holds multiple slabs, and database instances allocate slabs across multiple slab nodes to meet their predefined buffer pool capacity when they’re first started. The first allocated slab is nominated as the home node, and is assigned the responsibility of hosting the buffer cache metadata for the database instance. The Page Address Table (PAT) tracks the slab node and physical address of each page. The Page Invalidation Bitmap (PIB) is updated when a RW node has a local modification to a page which hasn’t been written back yet (and is used by RO nodes to know when they’re stale). The Page Reference Directory (PRD) tracks what instances currently hold references to each page described in the PAT. The Page Latch Table (PLT) manages a page latch for each entry in the PAT.

page_register is a request to the home node to either increment the refcount for the page and return its address, or allocate a new page (evicting an old one if necessary to make space) and return that. (This isn’t reading the page from storage, as there’s no direct Slab Node<->PolarFS communication, just allocating space on the remote buffer pool.) page_unregister decrements the reference count allowing the page to be freed if needed. Dirty pages can always be immediately evicted as PolarDB can materialize pages on demand from the ChunkServers. If the buffer pool size is expanded, the home node expands its PAT/BIP/PRD metadata accordingly, and allocates slabs eagerly. If the buffer pool size is shrunk, then extra memory is released by freeing pages, the exist pages are defragmented, and then the now unused slabs are released. Note that the defragmentation and physically contiguous memory is only needed to permit one-sided RDMA reads/writes, and a non-RDMA implementation could likely be simpler and non-contiguous.

Each instance has a local page cache in RAM, because there’s no L1/L2/L3 cache for remote memory. This local cache is tunable and defaults to \(min(sizeof(RemoteMemory)/8, 128GB)\), which was set by observing the effects on TPC-C and TPC-H benchmarks. Not all pages read from PolarFS are pushed into remote memory: pages read from full table scans are only read into the local page cache, and then are discarded. Modifications to pages are still performed only in local cache. If the page exists in the remote buffer pool, it must first be marked as invalidated before it can be modified, and before it can be dropped from the local cache it must be written back to the remote buffer pool (the flow of which is show in the diagram above). Insertions and deletions optimistically traverse the tree without locks, assuming they won’t need to split/merge any pages, and restart into a pessamistic locking traversal if it’s determined that it is necessary. (Interestingly in contrast to Socrates, which just has RO nodes restart their btree traversals whenever they encounter child pages of an older version than the parent page.)

There were a few improvements made to PolarDB, which are presented as seemingly unrelated to the disaggregated memory architecture, but I believe are a direct consequence. The snapshot isolation implementation was changed to utilize a centralized timestamp service, which is queried for both the read timestamp and commit timestamp. All rows have a commit timestamp suffixed to make MVCC visibility filtering easy, and a Commit Timestamp Log was added which records the commit timestamp of a transaction to allow resolving commit timestamps of recently committed data. The need for a remote timestamp service and tracking commit timestamp per row is so that promoting a Read-Only replica to the Read-Write leader doesn’t require scanning all the data. There’s no need to recover the next valid commit timestamp, as it’s held in a remote service. There’s no need to rebuild metadata of what transactions were concurrent shouldn’t see each others' effects, as MVCC visibility rules are a strict timestamp filter and rows without commit timestamps can be incrementally resolved. (This also results in a MVCC and transaction protocol which looks a lot like TiDB’s.) Similarly, PolarDB Serverless finally justified adding the GetPage@LSN request to PolarFS that every other disaggregated OLTP system already had (see, for example, the Socrates overview).

There’s a couple optimizations to transaction and query processing that they specifically call out. Read-only nodes don’t acquire latches in the buffer pool unless the RW node says it modified the B-tree structure since the Read-only node’s last access. They also implement a specific optimization for indexes: a prefetching index probe operation. Fetching keys from the index will generate prefetches to load the pointed-to data pages from the page servers, under the assumption that they’ll be immediately requested as part of SQL execution anyway.

In the event of the loss of the RW node, the Cluster Manager will promote a RO node to the new RW node. This involves collecting the \(min(max LSN per chunk)\) and requesting redo logs to be processed to bring all chunks to a consistent version. All invalidate pages in the remote memory pool are evicted (using the Page Invalidtion Bitmap so it’s not a full scan of GBs of data), along with any pages whose version is newer than the redo’d recovery version. All locks held by the failed RW node are released. All active transactions are recovered from the headers of the undo log. Then notifies the Cluster Manager its recovery is complete and rolls back the active transactions in the background. If a RW node voluntarily gives up its status as the writer to another node, it can flush all modified pages and drop all locks to save the RO node the work of applying redo logs and evicting pages from the buffer pool. In a drastic event where all replicas of the home slab are lost, all slabs are cleared, and all database nodes are restarted so that recovery restores a consistent state.

The evaluation shows the impact of all the above evaluations on recovery time. With no optimizations, unavailability lasted ~85s, and recovery back to original performance takes 105s. With page materialization on PolarFS, it’s reduced to an unavailability of ~15s and full performance after 35s. With remote memory buffer pool, it’s an unavailability of ~15s, and full performance after 23s. A voluntary handoff by the RW node leads to 2s of unavailability and full performance after 6s. Otherwise, the graphs show about one would expect that memory can be scaled elastically, and performance improves/degrates with more/less memory, respectively.

Discussion

They still undersold the RDMA difficulty. Someone who has worked with it previously commented that there’s all sorts of issues about racing reads and writes, and getting group membership and shard movement right is doubly hard. In both cases, an uninformed client can still do one-sided RDMA reads from a server they think is still a part of a replication group and/or has the shard it wants.

PolarDB-X

Wei Cao, Feifei Li, Gui Huang, Jianghang Lou, Jianwei Zhao, Dengcheng He, Mengshi Sun, Yingqiang Zhang, Sheng Wang, Xueqiang Wu, Han Liao, Zilin Chen, Xiaojian Fang, Mo Chen, Chenghui Liang, Yanxin Luo, Huanming Wang, Songlei Wang, Zhanfeng Ma, Xinjun Yang, Xiang Peng, Yubin Ruan, Yuhui Wang, Jie Zhou, Jianying Wang, Qingda Hu, and Junbin Kang. 2022. PolarDB-X: An Elastic Distributed Relational Database for Cloud-Native Applications. In 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), IEEE, 2859–2872. [scholar]

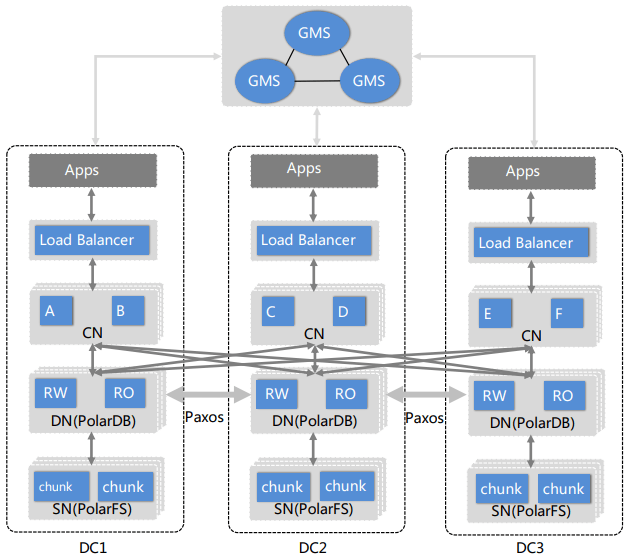

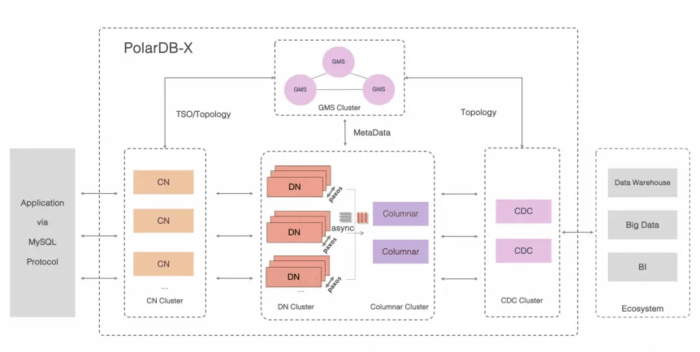

PolarDB-X is targeting three problems: cross-DC transactions, to extend PolarDB to more than one region; elasticity, by automatically adding read-only replicas and partitioning write responsibilities; and HTAP, by identifying and steering analytical and transactional queries to separate replicas. At a high level, PolarDB-X is the Vitess or Citus of PolarDB. Individual PolarDB instances become partitions in the broader PolarDB-X distributed, shared-nothing database. It is also open source, and available at polardb/polardbx. It seems in a very similar vein to the mostly un-published Amazon Aurora Limitless.

Above PolarDB, PolarDB-X adds a Load Balancer and set of Computation Nodes per PolarDB instance (DN & SN), with one Global Meta Service (GMS) for system metadata. The GMS is the control plane for PolarDB-X, and manages cluster membership, catalog tables, table/index partitioning rules, locations of shards, statistics, and MySQL system tables. The Load Balancer is the user’s entry point to PolarDB-X, which is exposed as a single geo-aware virtual IP address. The Computation Node coordinates read and write queries across the shards of tables stored in different PolarDB instances. For read queries, it decides if the local snapshot is fresh enough to avoid needing to go to a cross-AZ leader. For write queries, it manages the cross-shard transaction, if needed. It includes a cost-based optimizer and query executor, which it uses to break queries into per-shard queries, and apply any cross-shard evaluation needed to produce the final result. For an overview of the Database Node (PolarDB) or Storage Node (PolarFS), see their respective paper overviews above.

PolarDB-X hashes the primary key to assign rows to shards, by default. Not detailed in the paper, but the PolarDB-X Partitioned table docs describe that the supported partitioning strategies are: SINGLE, for unsharded tables; BROADCAST, for replicating the table on each shard; and PARTITION BY HASH, RANGE, LIST (manually assigned partitioning), or COHASH (HASH but multiple columns have the same value). Indexes can be defined as either global or local, where local indexes always index the data within the same shard. Tables with identical partition keys can be declared as a table group, and identical values will always result in the rows being stored on the same shard, thus predictably accelerating equi-joins.

The cross-DC replication is done by having PolarDB ship redo logs across datacenters. The replication is done through/in conjunction with a Paxos implementation managing the leadership and advancing of the Durable LSN as follows reply. Transations are divided into mini-transactions, and shipped incrementally in batches of redo logs (with other intermixed transactions). When the last mini-transaction of a user’s transaction is marked durable, the transaction has been committed.

To implement cross-shard transactions, PolarDB-X layers another MVCC and transaction protocol on top. They use a Hybrid Logical Clock to implement Snapshot Isolation. HLCs were chosen to not rely on tight physical clock synchronization, and do avoid the centralized clock server of a TiDB/Percolator-like approach. (Note that this does mean they technically sacrifice linearizability.) They include a few optimizations to reduce the number of times they bump the causality counter in HLCs, but otherwise, it’s a standard HLC and 2PC implementation. The public documentation instead describes the use of a Timestamp Oracle, and describes the GMS as serving that functionality to the Compute Nodes.

PolarDB-MT is an extension of PolarDB to natively understand multi-tenanting. A tenant is a set of schemas, databases, and tables. Cross-tenant operations are not permitted. A single PolarDB instance supports multiple tenants, and all operations are sent through the assigned RW node’s redo log. The tenant-to-RW-database-node mapping is stored in the GMS, and the RW node maintains a lease for the tenants it holds. Tenants can be transferred by suspending and transferring all active work and flushing dirty pages, then tranferring the lease. In the case of a failure, tenants can be split across other RW PolarDB instances, who divide the failed instance’s redo log by tenant and run recovery accordingly. What’s the difference between a shard and a tenant? The paper doesn’t answer at all. The public documentation on tenants describes it as a user-facing feature which is a performance isolated container for users and databases. It also seems likely that, much like Nile, tenants are used internally to binpack customers onto machines more efficiently.

PolarDB-X also powers an HTAP solution, where row-wise RW database nodes also asynchronously replicate into columnar Read-Only database nodes. (Which is a very TiDB/TiFlash take on HTAP.) A cost-based optimizer in the CN identifies OLAP queries, and dispatches them to the columnar database nodes. Portions of the analytical query are pushed down to the Storage Nodes (aka PolarFS), as an extension of the work described in PolarDB Computational Storage above. The Compute Node is nominated as the Query Coordinator, which breaks the query into fragments that can be distributed and executed on other Compute Nodes for parallel processing. Query execution is timesliced into 500ms jobs so that many queries may make progress concurrently. The threadpool for analytical processing work is placed under a cgroup to limit its resource usage, where as transactional processing is unconstrainted. The details on the analytical engine itself are published in the next paper: PolarDB-IMCI.

The evaluation section doesn’t hold any major surprises. They saw 19% higher sysbench throughput using HLCs rather than a timestamp oracle. Scaling operations complete within 4-5 seconds, without major distruptions. Having columnar data available improved the execution time of queries which highly benefit from columnstores.

PolarDB-ICMI

Jianying Wang, Tongliang Li, Haoze Song, Xinjun Yang, Wenchao Zhou, Feifei Li, Baoyue Yan, Qianqian Wu, Yukun Liang, ChengJun Ying, Yujie Wang, Baokai Chen, Chang Cai, Yubin Ruan, Xiaoyi Weng, Shibin Chen, Liang Yin, Chengzhong Yang, Xin Cai, Hongyan Xing, Nanlong Yu, Xiaofei Chen, Dapeng Huang, and Jianling Sun. 2023. PolarDB-IMCI: A Cloud-Native HTAP Database System at Alibaba. Proceedings of the ACM on Management of Data 1, 2 (June 2023), 1–25. [scholar]

PolarDB-IMCI is PolarDB’s solution to HTAP. It takes until the third page to finally learn that IMCI stands for in-memory column index. The goal of PolarDB-IMCI is outlined as achieving good OLAP performance, without compromising OLTP performance, on fresh, realtime data.

The in-memory column index is maintained on a set of read-only nodes separate from those executing OLTP workloads, so that OLAP and OLTP don’t interfere. Redo logs are used to apply updates to the columnar replicas, and PolarDB-IMCI introduces commit-ahead log shipping (CALS) and 2-Phase conflict-free log replay (2P-COFFER) to minimize the staleness of the columnar replicas and efficiently parse changes. The columnar index is maintained as append-only storage, making updates and lookups by RowID fast, but requires a second index (implemented as a two-layer LSM tree) for Primary Key to RowID mapping. IMCI’s checkpointing is integrated with the PolarDB storage engine, making it possible to spin up extra columnar replicas quickly.

A columnar index is defined as part of the DDL, which allows a subset of the rows of a table to be held in the in-memory columnar index. Tables are divided into chunks of 64K rows, and the indexed columns from these row groups are organized into a compressed data pack along with some metadata. The leftover rows form a partial data pack, which is left uncompressed due to the frequent udpates. The pack’s metadata offers zonemap-style metadata (min/max per column, sum, count, null, distinct) over the contained inserts. Deletes are treated as inserts of tombstones, which look up the RowID of the row being deleted by the Primary Key. An update is a delete followed by an insert. Compression is the standard columnar compression (frame of reference/delta encoding) and not deflate/lzma sort of compression.

Commit-ahead log shipping involves the Read-Write transaction node writing each DML statement out as a write-ahead log record once it has been executed. The columnar Read-Only nodes eagerly fetch this log record, parse it as a DML statement, and store it in a per-transaction buffer. Once the Read-Write node sends the final commit/abort decision, the Read-Only columnar nodes already have a buffer of logical operations to apply (if commit) or disacard (if abort). Transactions which overflow their buffer are pre-committed, and the MVCC implementation is used to hide the written data from being visible.

This work is all performed directly off of the redo write-ahead logs to avoid putting extra work on the read-write transactional node. However, redo logs reflect physical page changes and lack database-level or table-level information, page changes involve B+-Tree splits/merges as well, and only the page delta is included rather than the full update. The Two-Phase Conflict-Free Parallel Replay is to address these limitations. The first phase applies the redo logs onto an in-memory copy of the row-store to reconstruct the missing data and information. The second phase replays the full DML onto the column index, while respecting the original order of statement execution according to the LSNs in the redo log.

PolarDB-IMCI’s proxy layer plans the query under a row-based cost model. If the cost is low, it’s forwarded to the transactional replicas. If it’s high, it’s sent to a columnar replica, and re-planned to be column-oriented. This re-planning starts with the row-wise plan as its base, re-runs join ordering with the new cost model, and converts expression execution to be its vectorized equivalents. PolarDB-IMCI calculates table-wide statistics via random background sampling for use in accurate cardinality estimation in the optimizer.

The evaluation section shows significant speedups of PolarDB-IMCI over row-wise PolarDB for OLAP workloads, as one would expect of an in-memory columnar index versus an on-disk b-tree. They show performance that’s on the same order as Clickhouse, and then demonstrate the minimal impact to OLTP performance and the resource elasticity for OLAP workloads they’ve enabled.

PolarDB-SCC

Xinjun Yang, Yingqiang Zhang, Hao Chen, Chuan Sun, Feifei Li, and Wenchao Zhou. 2023. PolarDB-SCC: A Cloud-Native Database Ensuring Low Latency for Strongly Consistent Reads. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 16, 12 (August 2023), 3754–3767. [scholar]

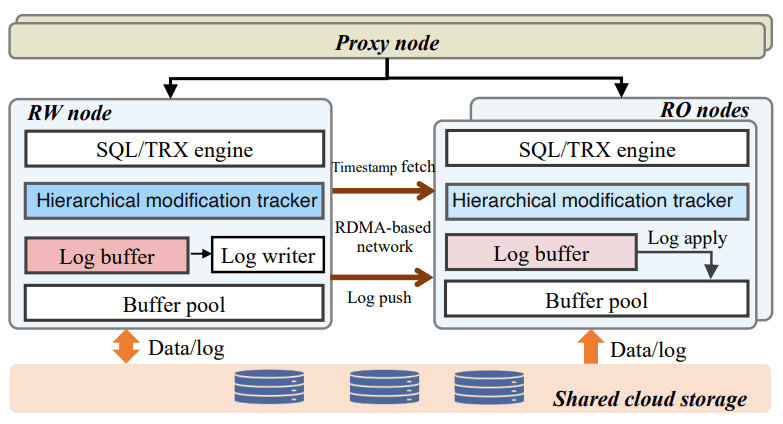

SCC stands for Strongly Consistent Cluster, and the focus of this paper is removing as much of the delay as possible between a Read-Write node committing a change and the Read-Only node becoming aware of and able to serve reads over it. They motivate the work with results that disaggregated databases' read-only replicas either have milliseconds of staleness on the read-only replicas, or that strongly consistent reads add 1x-5x additional read lattency. PolarDB-SCC uses three levels of timestamping (global, table, and page) to be able to begin pulling changes from read-write replicas sooner, and RDMA for minimizing the latency and overhead of doing so. This additional latency leads most databases to suggest sending all strongly consistent reads to the leader, thus defeating load balancing and making additional read-only replicas less useful. Allowing such workloads to be served from the read-only replicas is the exact problem PolarDB-SCC is targetting.

The timestamping scheme treats the read-write node as a timestamp oracle. On every modification it performs, it records a lamport clock for that modification at the global, table-level, and page-level granularity. A read-only node fetches the current timestamp at the start of a query, and it may batch this operation for many queries at once. Once the query has been assigned a timestamp, the read-only node may serve read results as long as all referenced global/table/page data is up-to-date locally. Due to the heirarchy, if e.g. the applied table-level timestamp is greater than the query’s timestamp, then it is implied that all of the pages are sufficiently up to date and do not need to be checked. The global timestamp is the maximum committed transaction’s timestamp. To avoid the overhead of maintaining an extra timestamp per page, the page’s Log Sequence Number is used as its timestamp. The Read-write node maintains the timestamps for tables and pages in hashtables, so that they may be quickly and easily queried over one-sided RDMA.

The paper goes into significant detail on the RDMA-based log shipping, which is essentially just a ringbuffer on either side with extra checks to make sure unconsumed log data being overwritten is handled correctly. The Read-Write node pushes its write-ahead logs into all of the Read-Only nodes. If any Read-Only node falls to far behind, it reads the logs from storage (PolarFS) instead. No changes were made to exist log buffer management.

Read-only queries within a transaction can also be sent to read-only nodes, but they must include the effects of writes performed earlier in the transaction. PolarDB-SCC accomplishes this by having the Read-Write node return the highest LSN generated as part of a write query to the proxy. The LSN is then attached by the proxy to subsequent read queries within the same transaction, so that the read-only node can ensure that it has the transaction’s writes applied. The load balancer will prefer sending queries to read-only nodes which have already applied up through the maximum write LSN locally.

The evaluation section shows that across SysBench and production workloads PolarDB-SCC delivers latency that’s just a fraction worse than stale reads from PolarDB Read-Only replicas. Additionally, throughput scales similarly with the stale reads workload, showing that it also burdens the Read-Write node notably less. It also permits better leveraging of read-only replicas for higher throughput on consistent queries. (The proxy and load balancer are not mentioned in the evaluation, but those components also existed previously as part of PolarDB, so it’s likely included equally on both sides.)

PolarDB Elasticity

One might notice that this overview refers to the paper and system described as "PolarDB Elasticity", whereas the paper itself calls it "PolarDB Serverless". This is because this is exactly the same name that they called PolarDB Serverless, the memory disaggregation paper. So to disambiguate the two, I’ve renamed the system.

Yingqiang Zhang, Xinjun Yang, Hao Chen, Feifei Li, Jiawei Xu, Jie Zhou, Xudong Wu, and Qiang Zhang. 2024. Towards a Shared-Storage-Based Serverless Database Achieving Seamless Scale-Up and Read Scale-Out. In 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), 5119–5131. [scholar]

Serverless database offerings require seamless migration of database instances to accomodate growing physical resource requirements, and dynamic scaling out of additional read-only nodes. A database instance being moved from one machine to another should not interrupt in-progress transactions, and should ideally have as minimal of a latency impact during the transition as possible. A seamless migration process can also enable seamless upgrades. For read scalability, this work relies upon PolarDB-SCC so that scaling out read-only nodes can offload strongly consistent read work from the primary, while minimizing the additional latency from replication delay. Note that the omission of write scalability from discussion was likely because it is covered by our next paper in the series, which was likely written and submitted concurrently with this publication.

PolarDB Elasticity introduces a proxy to maintain connections across the database instance migration process. The proxy node serves as a single unified endpoint which all applications connect to. ("Unified", as opposed to a design without PolarDB-SCC, where there would be a read-only stale endpoint and a read-write consistent endpoint.) A proxy connects to all read-only replicas for a database, and thus one application connection to the proxy may map to multiple different database instance connections. During database instance migration, the proxy buffers client requests, and forwards them once connections to the new database instance have been established.

Transaction migration allows migrating the undo/redo logs and in-memory transaction metadata for in-flight transactions to the new database instance so that in-flight transactions are not aborted upon migration. If a query is being executed when migration begins, the old instance will send the query’s redo logs to the new instance before acknowledging the query finished, to ensure that the new instance can take over the transaction execution. If an instance is terminated, the undo logs can be used to roll back the in-progress query, which can then be re-executed on the new node. Transaction locks are represented by rows being tagged with transaction IDs, and thus a new database instance taking ownership of a transaction also means takes ownership of all the transaction’s locks. The MySQL binlog isn’t required for recovery, but many customers depend on it for downstream CDC or processing, and thus the binlog is also migrated across instances during migration so that it may continue to be properly emitted.

The evaluation shows PolarDB database migration, as compared to Aurora Serverless, having superior migration speed and no transaction aborts. However, Aurora Serverless also focused heavily on the process of choosing good source/destination pairs of migrations to minimize movements, which this paper didn’t include in its scope. Similarly, PolarDB Elasticity mentions that it is offered in terms of PolarDB Capacity Units (PCUs) which is 1vCPU + 2GB of memory, and the corresponding networking and I/O, with resources allocated and deallocated in increments of 0.5 PCU. It similarly does not mention any details around how resource limits are monitored nor enforced.

PolarDB-MP

Xinjun Yang, Yingqiang Zhang, Hao Chen, Feifei Li, Bo Wang, Jing Fang, Chuan Sun, and Yuhui Wang. 2024. PolarDB-MP: A Multi-Primary Cloud-Native Database via Disaggregated Shared Memory. In Companion of the 2024 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD/PODS '24), ACM, 295–308. [scholar]

PolarDB-MP discusses extending PolarDB to support more than one Read-Write node. PolarDB is unique in implementing memory disaggregation first, and thus their multi-primary support is heavily based around already having a shared buffer pool accessible to all replicas over RDMA. Like all enjoyably spicy papers, PolarDB-MP begins by criticizing its related work: Aurora Multi-Master used optimistic concurrency control and suffered high abort rates, Taurus-MM used pessimistic concurrency control and suffered high overhead (8 nodes yielded a 1.8x throughput increase), and IBM pureScale and Oracle RAC are too expensive as they rely on custom dedicated machines.

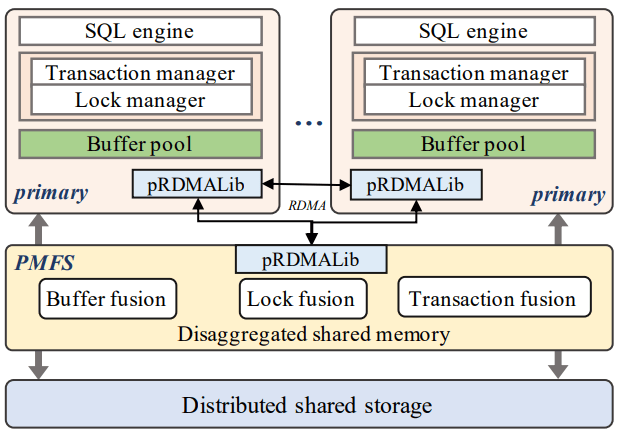

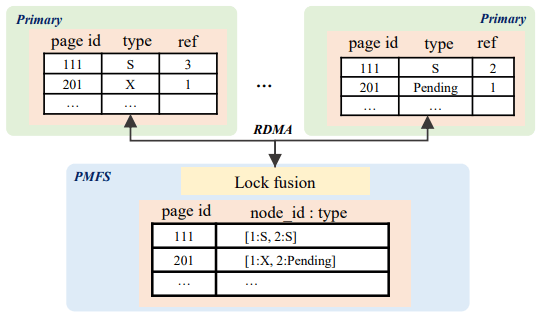

PolarDB-MP is centered around the Polar Multi-Primary Fusion Server (PMFS), which comprises Transaction Fusion, Buffer Fusion, and Lock Fusion, and doubles down on being highly RDMA centric. Transaction Fusion uses a timestamp oracle and allocates shared memory on each node for its local transaction data, which itself is also accessible to all nodes via RDMA. Buffer Fusion is the distributed buffer pool that all nodes share. Lock Fusion manages both page-level and row-level locking. PolarDB-MP also extends LSNs to Logical Log Sequence Numbers, such that each node may generate LSNs and there will be a global partial order between LLSNs.

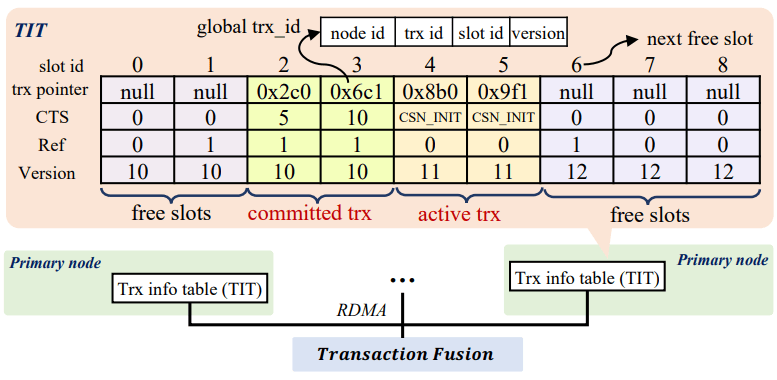

Transaction Fusion is a global timestamp oracle and per-node local transaction information to avoid centralized transaction information management. The paper puts forward an interesting argument that MVCC allowing reads to exist concurrently with writes, though generally being an advantage, poses a significant challenge to shared-storage multi-primary databases. Determining the correctly visible tuple out of many versions requires global transaction information, which imposes a high coordination overhead. The fix to this is to decentralize transaction management: every node maintains its local transaction’s information in a Transaction Information Table (TIT), which is accessible via RDMA for other nodes. The TIT maintains a pointer to the transaction object, its Commit Timesstamp (CTS), its version (a counter to differentiate TIT entries in the same position over time), and a flag named "ref" indicating if other transactions are waiting on this one to release its locks. Transactions are globally identifed by combining the node ID, transaction ID (populated from a node-local counter), slot number within the local TIT, and the TIT entry’s version number.

When updating a tuple, PolarDB-MP places the global transaction ID into the row’s metadata. At commit time, the CTS is updated if the row is still in the buffer, otherwise it is left as CSN_INIT. PolarDB is a MySQL derivative, so it relies upon the undo log reconstructing older values of rows for MVCC, and this process is unchanged for when the read tuple is too new for the given read version. When the row’s CTS is CSN_INIT, the global transaction ID can be used to fetch the TIT entry for the transaction. If the fetched entry does not match, it means that the transaction has already committed and the TIT slot re-used. TIT slots are garbage collected by a background thread, and entries are only removed when no active statement would need to read earlier than the committed transaction, and tso he minimum timestamp of any live transaction may be assigned to the row so that it is always visible. Read timestamps have their requests to the Timestamp Oracle coalesced as described in PolarDB-SCC and uses the same Linear Lamport Timestamp.

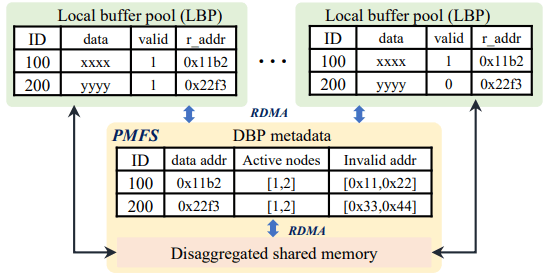

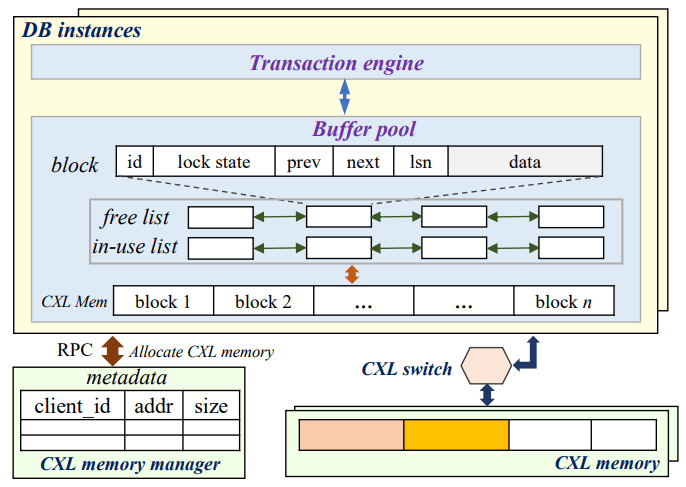

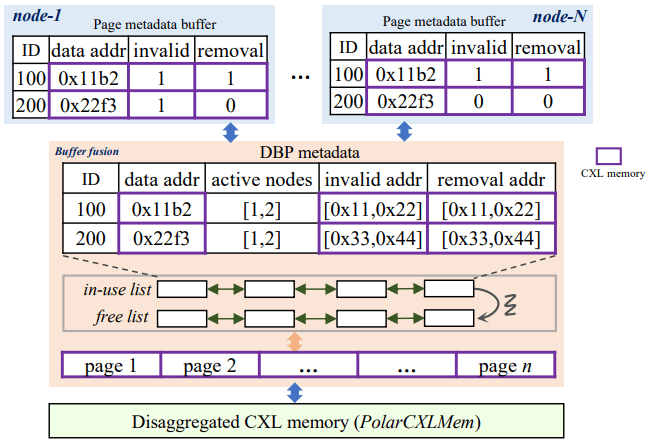

Buffer Fusion is a design for permitting low latency access to data pages by pushing them into a Distributed Buffer Pool (DBP). Each node maintains a Local Buffer Pool (LBP), which is a subset of the DBP. Each local buffer contains has metadata of the remote address of the buffer, and if the local buffer is valid. When an instance fetches a page from the DBP into its local buffer pool, it updates metadata in the DBP recording that it has a copy of the page. When an instance updates a page in its local buffer pool, it consults the DBP to find other nodes with the same page in their LBPs, and unsets the valid bit on them. Dirty pages in the LBP are flushed to the DBP in the background, but makes sure to force the corresponding logs to storage first so that the page is recoverable in the event of a failure.

Lock Fusion encompasses both the page-locking (PLock) and row-locking (RLock) protocols. The PLock is used to maintain atomic page access and structural consistency of the B-Tree, similar to a latch. Before performing any read or update of a page, the corresponding Shared or eXclusive PLock must be held. Each node tracks which PLocks it holds, and the reference count of the PLocks from each concurrently executing transaction. Locks are requested from the Fusion Server, and the Fusion Server notifies the awaiters when the PLock is released by a node. PLocks are speculatively held even after their local reference count drops to zero, under the assumption that locality means the same node is likely to re-request the same PLock. Structural changes to the B-Tree (splits or merges) are done while holding X-PLocks in the standard 2PL/2PC combo one would expect.

The RLock is used for transactional consistency. Locking information is embedded into the row itself as metadata, and only the waits-for relation is maintained on the Fusion Server, presumably for deadlock detection. Locking a row is done by writing the transaction’s ID into the corresponding field. Attempting to update a row means an X-PLock must already be held, so multiple primaries cannot try to update a row to lock it concurrently. If a transaction ID is already present, then it is a conflict, and the transaction must wait. The Transaction Information Table is then consulted (locally or remotely) to confirm that the RLock is held by an active transaction. A background processes synchronizes a minimal active transaction ID, to allow older transactions to be confirmed as completed without incurring remote TIT access costs. An RLock is always an exclusive lock in PolarDB-MP, there are no shared RLocks, relying on the fact that most reads come from read-only statements which may be served via MVCC locklessly.

Log Sequence Numbers are attached to each page modified, and are maintained similarly to a logical clock. When a page is read from storage or the DBP, the local LSN is potentially updated to ensure that it is equal to or greater than the read page’s recorded LSN. This ensures that updates to pages across different primaries produce redo logs that are merged into the right order when sorted by LSN.

In the evaluation, they show PolarDB-MP giving an 8x improvement with 8 primaries when the workload is fully partitioned, and a 3x improvement with 8 primaries when the workload has no partitioning. They also intentionally ran TPC-C incorrectly by setting think time and keying time to 0 and transforming it into a contention benchmark. A comparision is also done directly against Aurora’s Multi-Master and Taurus’s Multi-Master implementations, showing equal or better results. Performance of secondary index updates are compared with shared-nothing architectures where global secondary indexes are partitioned. Latency and throughput was shown to be better, largely due to RDMA usage, and I’m unclear what the point of the apples-to-oranges comparison was. A recovery test was performed to show that the loss of one primary does not affect the throughput of another primary.

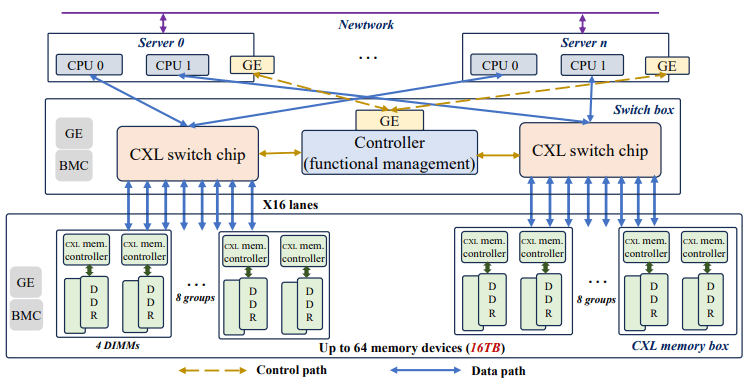

PolarDB-CXL

Compute Express Link (CXL) is a new interconnect techology for communication between processors and devices. Most notably for this work, CXL allows attaching a PCIe device of a CXL switch that enables multiple different hosts to share the same CXL-enabled DRAM devices. This puts it in direct competition with RDMA, and this paper is a comparison of CXL vs RDMA for building a memory disaggregated database. Section 2.1 provides a very nice overview of CXL, for at least what is relevant for the rest of the paper, and is well worth the read if you’re not already familiar with CXL.